BY JENNA ZHU

Here’s the scene: Summer of 2020. I am quarantining at home with my family. Outside, in the streets, Black Lives Matter (BLM) marches rage on. I am folding dumplings with my mother, listening to the first chapter of Robin diAngelo’a White Fragility, and my jaw drops hearing this passage:

White Fragility by Robin diAngelo has become a widely-read title in the wake of Black Lives Matter protests of the summer.

When I talk to white people about racism, their responses are so predictable I sometimes feel as though we are all reciting lines from a shared script. And on some level, we are, because we are actors in a shared culture. A significant aspect of the white script derives from our seeing ourselves as both objective and unique. To understand white fragility, we have to understand why we cannot fully be either; we must understand the forces of socialization.

In the immortal words of Christine Sydelko, I was shooketh. diAngelo’s book, a searing take on why grappling with anti-Black racism is “so hard for white people,” but she was also describing something I had seen among in my own people. As an Asian American woman, and active supporter of the BLM movement, I recognized her descriptions about speaking across lines of positional privilege. Last fall, I had been in a show about anti-Blackness amongst Asians and its many forms, including colorism and intergroup stereotyping, but those truths hit even harder now.

I began to wonder if there was such a thing as “Asian fragility.” Though it does not look exactly the same as “white fragility,” nor occurred in the same the circumstances, the reaction that she was describing was exactly the same. The knee-jerk defensiveness. The quick dismissal of personal responsibility. The refusal to acknowledge that one’s own race might have an inherent advantage. And more insidious: the what-about-us-isms. The Olympics of Oppression. Bootstrap theory. Victim blaming. And just plain denial.

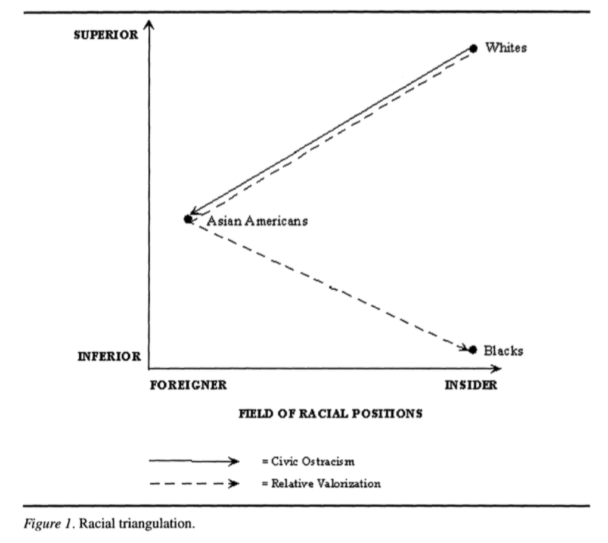

Thinking back to my own upbringing, I realized that this was, in fact, nothing new. From my own buying into the “model minority myth” to the controversy over Fisher vs. University of Texas, I had profited from this inherently racist system. By being non-Black, I had assimilated as the “middleman minority,” and I wondered how my AAPI privilege came to resemble white privilege so much. Claire Jean Kim posits that Asian Americans occupy a position of relative superiority while also maintaining a designation of “foreignness” relative to African Americans, something that the coronavirus pandemic has made all too clear. Nevertheless, this disparity arose from our patterns of arrival, slavery versus choice (with varying degrees of welcome): that difference is critically sewn into the fabric of how the two communities have progressed over time, with many historical shifts that have further widened this gap between them.

Graphic from “The Racial Triangulation of Asian Americans” by Claire Jean Kim. Politics and Society, March 1999.

When I began to have this conversation with my parents, I was met with resistance on every level: from the subject matter at hand, to engaging in the conversation at all, to dealing with our difficult emotions in unhelpful ways. Frankly, at first I was livid. Black people were dying, and we had the privilege to stay at home and to not be killed for walking outside if we so desired. Granted, there is a generational and cultural barrier to understanding, but I still could not fathom how much they clung to the past. However, as time went on, I noticed that underneath the conversation, lay something else that wasn’t about BLM or empathizing with the struggle -- it was about justifying their own life choices.

There were a few tells. First, I noticed that they cast me as the spokesperson for my entire generation and for the political left, despite my declaring that I can only speak for myself. Second, I noticed that there was a desperate, even violent desire to protect their right to hold “neutrality” and to not choose a side. As Steve Biko said, “the most potent weapon in the hands of the oppressor is the mind of the oppressed.” Having grown up during the Cultural Revolution, my parents tend to see extremism as a type of oppression. But what when the extremism is anti-racism? Was their desire to believe racism does not exist, or that they are not racist, achieving the opposite? The answer, as I soon found out, was indeed both/and.

I began to investigate the history of Asian American migration: the gap between their arrival, and my current radicalism.

This photo of Anna Sun went viral following the protests held in wake of Michael Brown’s death in 2015.

I interviewed Dr. Catherine Fung, an Asian-American studies scholar, from whom I learned that all major civil rights battles have been won through coalition building, from Bacon’s Rebellion to the Third World Liberation Front, and the histories of all communities of color in the U.S. are deeply intertwined. In fact, the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965, which led to the influx of AAPI migrants who now characterize the “model minority” (often highly-educated and possessing social capital upon entry), was only passed because of the civil rights movement.

When I approached my parents about this again, much later, all of us less-heated, they told me that their first twenty years in the States was just about survival, including providing a home for me to live in. For that, I am grateful. I also understood that my awareness of my privilege was a privilege in and of itself, and I began to drop my expectations of change. After all, when one is used to little, it is natural to want to protect it at all costs, whether it be privilege or material wealth.

While on the surface it may seem as if Asian Americans occupy a “middle space”, as Bell Hooks famously writes, there is no hierarchy of oppressions. Refusing to buy into the scarcity mindset and individualism of white supremacy culture allows us to stand together and take collective action.

I stand for the anti-fascist work of Fang Fang, author of Wuhan Diary as much as I do for Black Lives Matter. Anti-oppression and anti-racism go hand-in-hand, as Angela Davis teaches, and you can’t have one without the other. After all, what is racism if not the failure to invest in our shared liberation?

About the Author:

Jenna Zhu is an actress, activist, and anti-racist facilitator based in Los Angeles. She was last seen onstage in the U.S. premiere of "White Pearl" by Anchuli Felicia King at Studio Theatre, which deals with anti-Blackness in Asia. She began co-facilitating workshops on anti-racism for allies this summer through the NoMarking Society: with casting director Kate Lumpkin, and she is co-leading a second round by donation through the Actor's Center. She is a proud first-generation Chinese American and Canadian from Dallas, TX and Ontario, Canada.

Images provided by author or used under creative commons license.